Aspen Festival Orchestra

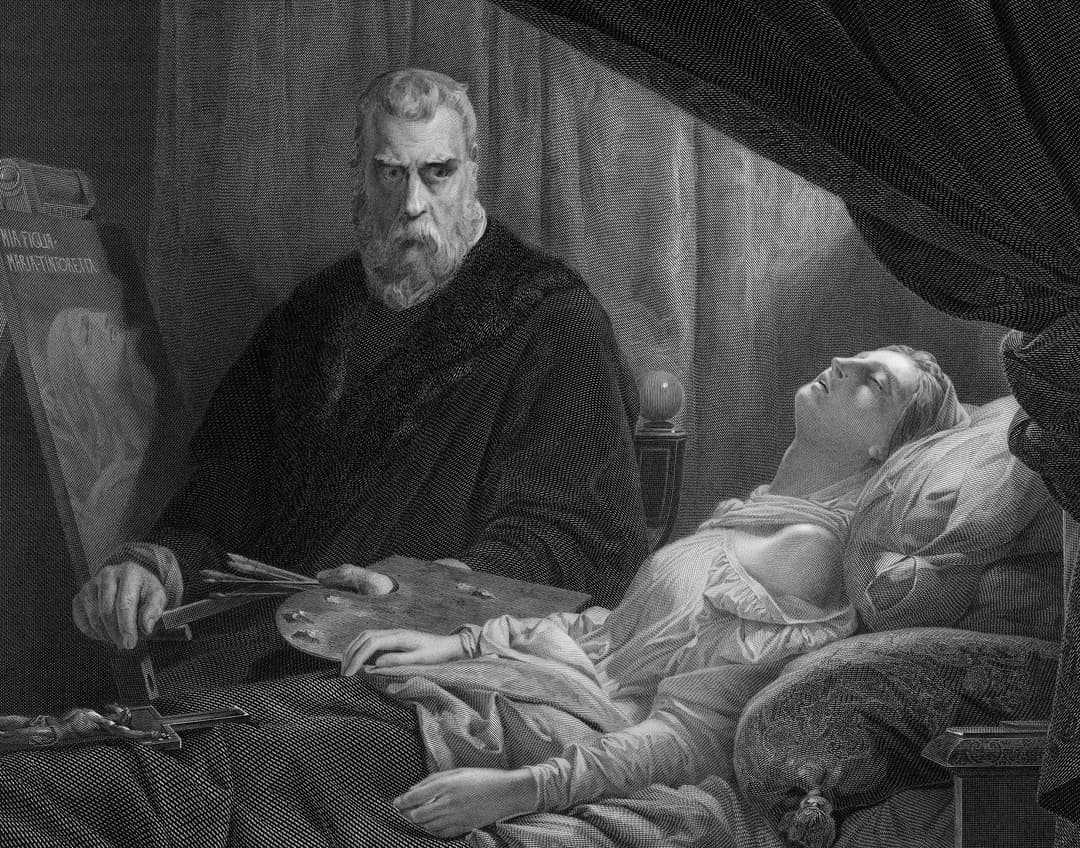

Tintoretto at his Daughter’s Deathbed, after 1843 (engraving) by Achille Martinet after Leon Cogniet. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. This painting depicts the Renaissance master Tintoretto in the year 1590 as he immortalizes his daughter in his art as she lies on her deathbed.

Richard Strauss

Tod und Verklärung (Death and Transfiguration), op. 24

Richard Strauss was born in Munich on June 11, 1864, and died in the Alpine ski town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen on September 8, 1949. (Aspen’s Garmisch Street is named after this town.) He began composing Tod und Verklärung in the late summer of 1888, completing the score on November 18, 1889. Strauss himself conducted the first performance at the Eisenach Festival on June 21, 1890. Strauss’s score calls for three flutes, two oboes and English horn, two clarinets and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, bass tuba, timpani, tamtam, two harps, and strings.

Richard Strauss’s early musical education was classically oriented, emphasizing composers up to Mendelssohn but hardly going beyond. Then he met Alexander Ritter, a violinist, composer, and ardent Wagnerian who introduced the young Strauss to the modern German composers. It was thanks to Ritter’s influence that Strauss conceived his entire youthful series of tone-poems before turning his attention almost totally to opera.

The transition from life to death seems an unlikely subject for a composer of barely twenty-five years, but although the depiction of the dying man’s physical condition and torments are astonishingly vivid (and even in some sense realistic), the real point of the work is that its subject is an artist who, in the composer’s words, “had striven towards the highest idealistic aims” and who ultimately, in death, is transformed. Strauss was likely thinking of himself here; he always had a tendency to identify with his creations, and particularly with the image of the artist constantly in search of higher planes of activity. For his vivid conception of the dying man’s physical weakness and mortal illness, Strauss composed music that might be called an opera for orchestra, expressing every aspect of the scene in a form that owes little to instrumental music.

Strauss was concerned that his audience would not understand the music if they did not have a detailed account of the images he intended to convey, and he made sure to print Ritter’s sixteen-line poetic treatment of his scenario on the title page of the score. But it is his own prose scenario, written in a letter of 1894, that provides the best guide. He endeavored to express “in the form of a tone poem the dying hours of a man who had striven towards the highest idealist aims, maybe indeed those of an artist.” The sick man’s uneasy sleep, marked “with heavy irregular breathing,” is interrupted by “friendly dreams . . . he wakes up; he is once more racked with horrible agonies; his limbs shake with fever.” Once the agonies pass, his life flashes before his eyes: first childhood, “the time of his youth with its strivings and passions and then . . . there appears to him the fruit of his life’s path, the conception, the ideal which he has sought to realize, to present artistically, but which he has not been able to complete, since it is not for man to be able to accomplish such things. The hour of death approaches, the soul leaves the body in order to find gloriously achieved in everlasting space those things that could not be fulfilled here below.”

After an extended slow introduction, the work is cast (as the title suggests) into two principal sections: an Allegro depicting the dying man’s refusal to “go gentle into that good night,” and a later moderato portion that illustrates the transformation of his lifelong ideals into warm nobility after

his death.

Though the dying figure on the bed lacks great strength, Strauss’s successive themes make clear that he is nonetheless a man of vivid personality. They are by turns warm and romantic or evocative and childlike. But the sufferer wills himself to withstand his illness, and he persists despite a violent attack of convulsions. He is not about to yield easily to death. Following a defiant struggle with his illness, he collapses again. At this point Strauss introduces the major theme of the work, one he identified with the artist’s creativity and idealism. This is heard only briefly at first, but it returns several times in progressively more promising guises as a way of suggesting that the artist’s vision is growing more precise and clear even as he approaches the fatal moment. The irregular heartbeat signals the inevitable end. Strauss then sets himself the nearly impossible task of depicting a soul gloriously transformed after the moment of death, with two themes in particular reworked in new guises, soaring ever higher.

Nearly six decades later, as the composer himself lay dying at an advanced age, he announced to his daughter-in-law, “Death is just as I composed it in Tod und Verklärung!”

— © Steven Ledbetter

Scheherazade, c. 1850–1900 (oil on canvas) by Sophie Gengembre Anderson. New Art Gallery Walsall/Wikimedia Commons.

Maurice Ravel

Shéhérazade

Joseph Maurice Ravel was born at Ciboure, France, on March 7, 1875, and died in Paris on December 28, 1937. He composed Shéhérazade to poems of Tristan Klingsor in 1903, creating both a version with piano accompaniment and one with orchestra. Alfred Cortot conducted the premiere on May 17, 1904, at a concert of the Société Nationale. The soloist was Jane Hatto. In addition to the soprano soloist, the score calls for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes and English horn, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, two harps, and strings.

It is clear that a poet who would choose the pen name Tristan Klingsor, taking the names of principal characters from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and Parsifal, must be a staunch admirer of Wagner, and perhaps equally clear that he would be drawn into artistic circles with composers. Such was the case with Arthur Justin Léon Leclère (1874–1966), who was also a musician and artist and whom Ravel met via a recently formed group of self-described artistic outcasts calling themselves Les Apaches, a slang term in Paris for underworld hooligans. The meetings were filled with excitement and high enthusiasm for novelty in the arts. Many of Ravel’s works grew out of his connection with people he met there.

The three orchestral songs published as Shéhérazade are the principal fruit of Ravel’s friendship with Klingsor. The work came in the pivotal year 1903 on the heels of two negative experiences. Ravel had submitted his String Quartet for the composition prize at the Conservatoire, but the faculty judges found it insufficient and he was expelled. (They would no doubt be astonished to know how often it is performed today.) Secondly, he failed in his fourth attempt to win the Prix de Rome. In that same year Tristan Klingsor published a collection of one hundred poems evoking the mystery and allure of the East under the title Shéhérazade. Frenchmen had been increasingly fascinated by the Middle East ever since Napoleon’s incursion into Egypt a century earlier. The great Paris Exposition of 1889, which saw the opening of the Eiffel Tower and presentations of music from all over the world, only increased Parisians’ Orientalist furor. Two of the symbols frequently appropriated by the Orientalism of the time were the Thousand and One Nights and its heroine Scheherazade, whose name adorns Klingsor’s collection.

Music and poetry had been the subject of many discussions in meetings of the Apaches, so it is hardly surprising that Ravel should choose to create some specific examples. He was particularly interested in the subtle free verse of these poems, which presented a stark contrast to the tightly contained metrical effects of most poems written to be set to music. They were also much more challenging to the composer for that reason. But Klingsor’s texts provided an additional aid to the imagination in the form of vivid images, which Ravel captured in equally vivid musical colors. Ravel had already heard Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, from which he learned something about the setting of prose texts, but his lines are nonetheless more lyrical and less recitative-like than Debussy’s.

Asie (Asia), the first song, is a sweeping fantastic tour of the Orient underscored by a symphonic flow built primarily on two themes, the one first heard in the oboe and the second in the clarinets. The result is a vivid and kaleidoscopic tone painting. La flûte enchantée (The Enchanted Flute) expresses the impassioned thoughts of a slave girl waiting by her sleeping master while she hears her lover playing a flute outside her window. L’indifferent (The Indifferent One) is a luxuriantly sensuous song from a narrator of ambiguous gender depicting an immediate physical attraction that fails to lead to the desired result. Both of the last two songs are much shorter and simpler than Asie; all three, though, capture what Ravel himself called “the freshness of youth.” — © Steven Ledbetter

Landscape, c. 1880 (watercolor on cardstock) by Leopold Gmelin. Architecture Museum of the Technical University, Munich.

Felix Mendelssohn

Piano Concerto No. 1 in G minor, op. 25

Jacob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn was born in Hamburg, Germany, on February 3, 1809, and died in Leipzig on November 4, 1847. The G minor Piano Concerto was completed in 1831 and received its first performance in the Odeonsaal in Munich on October 17 of that year with the composer as soloist. In addition to the solo piano, the score calls for two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, and trumpets, as well as timpani and strings.

Felix Mendelssohn was an accomplished pianist and needed no encouragement to exploit to full advantage the larger sound and technical advances of the early nineteenth-century piano. The weight and size that was now possible allowed the piano to hold its own alongside the contemporaneous symphony orchestra, and its upper range was sharper, clearer, newly capable of prominent arpeggios and flourishes. As he returned from Italy, Mendelssohn was poised to make the most of these new advances in musical technology.

For all Mendelssohn’s popularity, his G minor Concerto has never quite held as prominent a place in concert programs as the Hebrides Overture and the Italian Symphony, which were composed at about the same time as the concerto. But this has only been true for the last century or so. A century and a half ago, the Mendelssohn Concerto was constantly in the repertory, as popular with players as it was with audiences.

In all of his concertos Mendelssohn made some intriguing, even daring adjustments to the traditional and well-established concerto form, though the G minor Concerto is admittedly less unorthodox than the Second Piano Concerto or the Violin Concerto. Yet Mendelssohn already seeks to avoid the intrusive breaks between movements that interrupt the musical flow with silence or (in the concerto performances of his day) applause. He composed the score so that all three movements would run directly into one another. Beethoven had already linked the last two movements in his fourth and fifth piano concertos, but Mendelssohn seems to be the first composer to connect all three.

Mendelssohn borrowed another idea from Beethoven’s last two concertos in making the soloist enter early in the work. But he took the idea a giant step further by fusing the orchestral and solo ritornello statements into a single passage, thus projecting the pianist more forcefully than other concertos of his time were likely to do. The bright E major of the middle movement is a striking contrast to the darkness of G minor at the opening of the Concerto. The piano briefly suggests another Beethoven influence right at the beginning of the slow movement, when it introduces a thematic idea with the same rhythmic pattern as the slow movement of the Beethoven Violin Concerto. The final rondo has a rhythmically precise presto introduction (more Beethovenian effects here) and a brilliant rondo theme in G major that brings the Concerto to its lively close. For all it might seem that Mendelssohn is exploiting his evident model in the Beethoven concertos, his Opus 25 is still much more than youthful imitation; its combination of brilliance, energy, and warmth reveal an extraordinarily gifted twenty-two year old in the fine flush of his maturity. — © Steven Ledbetter

The Storm, 1880 (oil on canvas) by Pierre-Auguste Cot. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe collection.

Maurice Ravel

Daphnis et Chloe Suite No. 2

Sergei Diaghilev commissioned the ballet Daphnis and Chloe in 1909; the piano score was published in 1910. Ravel completed the full score in 1911, though the present form of the work was not ready until April 5, 1912. Pierre Monteux conducted the first stage performance at a production by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes at the Châtelet on June 8, 1912. The score calls for two flutes, alto flute, and piccolo; two oboes and English horn; two clarinets, E-flat clarinet, and bass clarinet; three bassoons and contrabassoon; four horns, four trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, wind machine, celesta, glockenspiel, two harps, and strings.

Margaret Drabble, writing in the Oxford Companion to English Literature, calls the literary source for Ravel’s ballet Daphnis and Chloe “the finest of Greek romances.” The tale, written in prose by a shadowy author known only as Longus (whose dates can only be estimated as second or third century C.E. through the problematic device of stylistic analysis), is unusual among Greek stories for its attention to character. The setting was an idealized landscape of shepherds and shepherdesses, nymphs and satyrs—a tradition going back in lyric poetry to Theocritus (third century B.C.E.); it had a long history in post-Classical literature as well. Typical Greek romances involve a potential love relation that is thwarted by some obstacle, often the carrying off of the maiden by a band of pirates, which is inevitably followed by her rescue by the hero to reunite the couple at the predictable end where all obstacles are overcome.

Daphnis and Chloe has some of these elements, to be sure, but the emphasis is elsewhere: on a psychological description of the passion that grows between Daphnis and Chloe, two foundlings raised by shepherds on the island of Lesbos, from their first naive and confused feelings during childhood to full sexual maturity. So powerful is Longus’s psychological analysis—and his description of the sex act—that the book has been regarded as pornographic throughout much of literary history. These circumstances, Drabble maintains, have kept Daphnis and Chloe from receiving the critical attention that its “charm and genuine artistry” would normally have won for it.

Ravel was commissioned to write Daphnis and Chloe, his largest and finest orchestral score, in 1909, before the Ballets Russes had become established in Paris’s artistic vanguard. It took until May 1910 for him to complete a piano score; he substantially reworked the finale in 1911 and completed the scoring later that year. The problem then was to mount the work on the stage, which did not come to pass until June 1912.

Daphnis and Chloe is entirely different from typical ballets of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Rather than consisting of isolated numbers decreed by the choreographer, this score is symphonically constructed. Ravel drew two suites out of the score, essentially using each of the two main parts as a single orchestral number.

During the first part (not performed tonight), the nymph Chloe had been seized by pirates and carried far from her lover Daphnis, who prays to the god Pan for assistance. Darkness falls; in the pirates’ camp, they celebrate their successful raid in a wild drunken dance. Pan appears in response to Daphnis’s plea. True to his name, he casts the spell of “Pan-ic” on the pirates, who run in terror. Chloe is released and set free to be returned to her home.

Suite No. 2 opens with Ravel’s brilliantly achieved depiction of dawn in the grotto where Daphnis sleeps. Birds sing, the waterfall splashes, and the sun gradually penetrates the mists. Shepherds find Daphnis and awaken him. He looks around seeking Chloe, and sees her arriving at last. They throw themselves into one another’s arms.

An old shepherd Lammon explains to them that if Pan did indeed help them, it was in remembrance of his lost love for Syrinx. Daphnis and Chloe mime the story of Pan and Syrinx: Pan expresses his love for the nymph Syrinx, who, frightened, disappears in the reeds. In despair, Pan forms a flute out of a reed and plays upon it to commemorate his love. During the ravishing flute solo, Chloe reappears and echoes the music of the flute in her movements. The dance becomes more and more animated. At its climax, Chloe throws herself into Daphnis’s arms, and they solemnly exchange vows before the altar. A group of young girls dressed as bacchantes enter with tambourines. Now the celebration can begin in earnest, in the extended Danse générale, one of the most brilliant and exciting orchestral passages ever written.

— © Steven Ledbetter

Fabien Gabel is music director of Lower Austria’s Tonkünstler Orchestra, leading concerts across the orchestra’s homes in St. Pölten, Grafenegg, and the Vienna Musikverein. He has established an international career of the highest caliber, appearing with orchestras such as Orchestre de Paris, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, London Philharmonic, the Cleveland Orchestra, NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchester, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, Seoul Philharmonic, and Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. Praised for his imaginative programs, Gabel crafts eclectic combinations of beloved masterworks and lesser-known gems of the repertoire. The 2025–2026 season is marked by important collaborations: Gabel debuts at the Metropolitan Opera with Carmen; leads a five-city tour of Spain with Yuja Wang and the Mahler Chamber Orchestra; and conducts premiere performances of Samy Moussa’s Concerto for Flute and Orchestra with soloist Emmanuel Pahud and both the Orchestre National de France and the Detroit Symphony, as well as Donghoon Shin’s viola concerto Threadsuns with both the Minnesota Orchestra and the Tonkünstler Orchestra. Additional highlights include returns to the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Orquesta Sinfónica de Galicia, Stavanger Symphony, Toronto Symphony, BBC Symphony Orchestra, and the Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg. He makes his South American debut with the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra and debuts at the Tongyeong International Music Festival and with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

Grammy Award-winning soprano Ana María Martínez has captivated audiences worldwide with her artistry and versatility. The 2024–25 season sees her star in Los Angeles Opera’s premiere of Osvaldo Golijov’s Ainadamar as Margarita Xirgu and as Despina in their production of Così fan tutte. She also makes her house debut with Pittsburgh Opera in the title role of Tosca and returns to Houston Grand Opera for a cameo appearance in West Side Story. A celebrated interpreter on the stage, she has portrayed leading roles at the Metropolitan Opera, Royal Opera House, Vienna State Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and San Francisco Opera. Her repertoire includes Carmen, Madama Butterfly, Don Giovanni, Rusalka, and La bohème. She has worked with orchestras like the Berlin Philharmonic and New York Philharmonic, and made her La Scala debut with Gustavo Dudamel. Originally from Puerto Rico, Ana María Martínez is a graduate of The Juilliard School and the Houston Grand Opera Studio. As the inaugural Artistic Advisor at Houston Grand Opera and a voice professor at Rice University, Martínez continues to inspire emerging artists. Beyond performing, Martínez is a contributor to Classical Singer Magazine and has been featured in Cathy Areu’s book Latino Wisdom.

Seong-Jin Cho has established himself as a leading pianist of his generation and one of the most distinctive artists on the current music scene. With innate musicality and consummate artistry, his thoughtful, poetic, virtuosic, and colorful playing combines panache with purity and is driven by an impressive natural sense of balance. Seong-Jin Cho caught the world’s attention in 2015 when he won first prize at the Chopin International Competition in Warsaw, and his career has rapidly ascended since. In 2023 Cho was awarded the prestigious Samsung Ho-Am Prize in the Arts. An artist in high demand, Cho works with the world’s most prestigious orchestras, including the Berlin Philharmonic, Vienna Philharmonic, London Symphony, Concertgebouw, and Boston Symphony. In the 2024–25 season Seong-Jin Cho took up the mantle of artist-in-residence with the Berlin Philharmonic. Highly sought-after in recital, Seong-Jin Cho appears in the world’s most prestigious concert halls. This season he presents the complete solo piano music of Maurice Ravel at venues including the Wiener Konzerthaus, Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, Barbican Centre London, Celebrity Series at Boston Symphony Hall, Walt Disney Hall Los Angeles, and Carnegie Hall. Seong-Jin Cho’s latest recording for Deutsche Grammophon, which was released this spring, presents Ravel’s complete solo piano works and concertos together with the Boston Symphony and Andris Nelsons. Born in 1994 in Seoul, Seong-Jin Cho became the youngest-ever winner of Japan’s Hamamatsu International Piano Competition in 2009. He has studied with Michel Béroff and is now based in Berlin.