Aspen Conducting Academy Orchestra

The Lower East Side, c. 1914 (oil on canvas) by Samuel Johnson Woolf. Photo © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images.

Jessie Montgomery

Coincident Dances

Jessie Montgomery was born in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, New York, on December 8, 1981, and currently teaches composition and violin at the Mannes School of Music. Inspired by a New York City soundscape, Coincident Dances was commissioned by the Chicago Sinfonietta and received its premiere on September 16, 2017, at Wentz Concert Hall in Naperville, Illinois. The work is scored for two each of flutes (one doubling piccolo), oboes, clarinets (one doubling bass clarinet), bassoons, horns, and trumpets; three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, and strings.

The world today is a complicated place, and musical beauty sometimes seems out of step with it. While some individuals and some societies keep thriving, many more face unrelenting struggle that makes hope a rare luxury. Poverty, hunger, racism, and political turmoil are the everyday experience of millions. What can music say or do about that? It might seem that artistic activity does not contribute much to social or political transformation, but generations of artists have persuasively demonstrated the actual potential of the arts to turn the world into a better place, little by little, sometimes one human being at a time. The music of Jessie Montgomery, and her orchestral work Coincident Dances in particular, is beyond eloquent in that regard. Regardless of how different her style seems to be in comparison to that of Ella Fitzgerald, Sonny Rollins, or Nina Simone, she shares with them an approach to music as a form of social activism, as a tool for advocacy and inclusion.

The work was inspired, she explains, by the diverse musical soundscape of New York City, and by the way in which two or more different styles might be intertwined in a single listening experience. Thus “the orchestra takes on the role of a DJ of a multicultural dance track.” At one moment in the piece, Brazilian samba and techno sound right alongside a French horn blaring out the famous Brindisi (Drinking song) from Verdi’s opera La traviata; in another Zimbabwean mbira can be heard; Jazz and electronic dance music intermingle elsewhere; the alert listener can even pick out and identify the Colombian dance genre called cumbia. At various points during the composition it is possible to appreciate the simultaneity of different ideas, presented either as melodic lines or rhythmic structures, as if recreating—or reenacting—the listening experience of one moving through New York City. After an extended introduction in the strings, for example, two musical phrases share the spotlight that, on first impression, do not seem to have anything to do with each other: on the one hand a chromatic ostinato (a repeated phrase) built on a Blues scale and combining strings with bass clarinet, and on the other a melodic incursion by bassoon and clarinet in its altissimo register (very high range). At first this melody appears to clash rhythmically with the ostinato, but it eventually merges with it in a delightful display of counterpoint. The subsequent work of orchestration is creative and courageous. While each melodic cell is supported by harmonic and rhythmic groupings in the orchestra, this happens through the risky articulation of a multiplicity of timbres, rhythms, sudden incursions, and polyphonic fills of various sorts—including the pairing of percussion and horns, and then of strings, vibraphones, and horns. These passages are at once tempestuous and intense before closing suddenly with a soothing cascade of melodic echoes.

Beyond these musical details, however, Coincident Dances conveys an unmistakable sense of hope. While social activism may take many forms, finding some common ground to cope together, listening and caring for each other as we deal with our respective challenges, might yet be a powerful intervention. And in that music has an indispensable role to play. — © Sergio Ospina-Romero

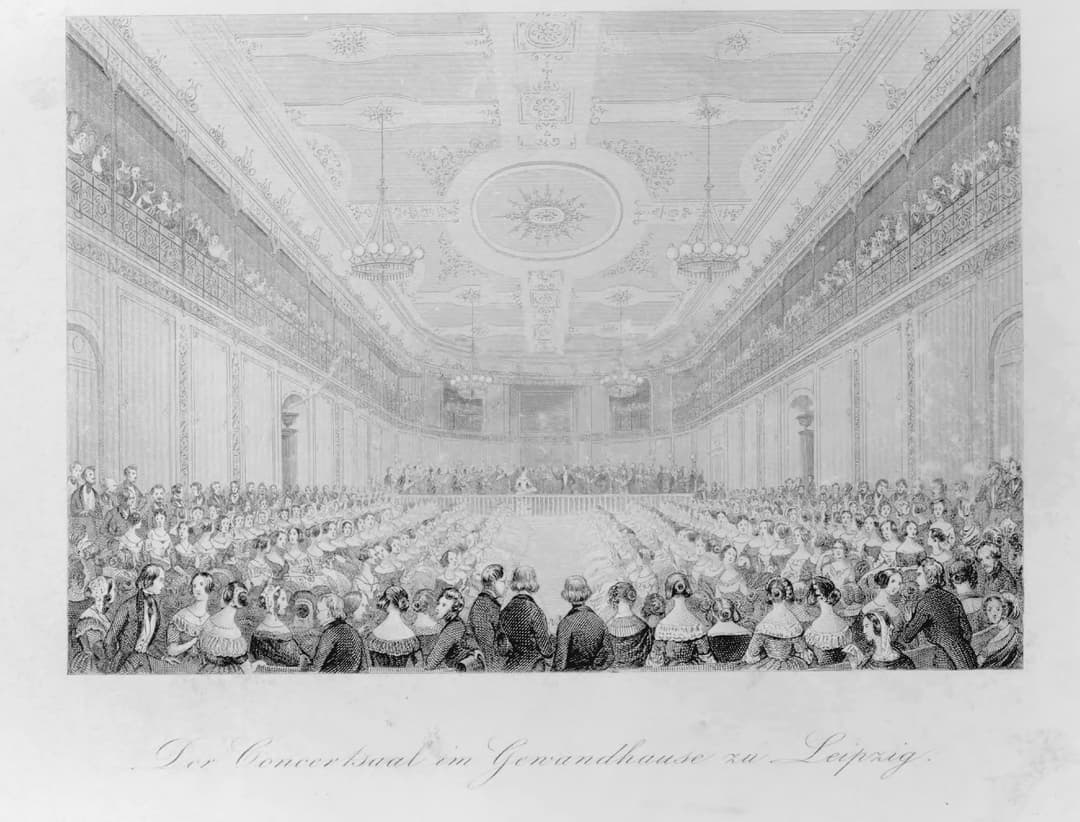

Leipzig Gewandhaus Concertsaal, before 1899, from an album collected by Leo P. Wheat. Library of Congress, Music Division.

Felix Mendelssohn

Violin Concerto in E minor, op. 64

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn was born in Hamburg on February 3, 1809, and died in Leipzig on November 4, 1847. He planned a violin concerto as early as 1838, but it was not until 1844 that he settled down to serious work on it; the finished score is dated September 16, 1844. The first performance took place in Leipzig under Niels Gade’s direction, with Ferdinand David as the soloist. The Concerto is scored for solo violin with an orchestra consisting of pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, and trumpets, as well as timpani and strings

Ferdinand David (1810–1873) was one of the most distinguished German violin players and teachers of his day. When the twenty-seven-year-old Felix Mendelssohn became director of the Gewandhaus concerts in Leipzig in 1836, he had David, just a year his junior, appointed to the position of concertmaster. Relations were always cordial between composer and violinist, and their warmth was marked in a letter that Mendelssohn wrote to David on July 30, 1838, in which he commented, “I’d like to write a violin concerto for you next winter; one in E minor sticks in my head, the beginning of which will not leave me in peace.”

But having said as much, Mendelssohn was in no hurry to complete the work. He sketched and drafted portions of it in at least two distinct stages over a period of years. His correspondence with David is sometimes filled with discussions of specific detailed points of technique and sometimes with the violinist’s urgent plea that he finish the piece at last. In July 1839 Mendelssohn wrote to David reiterating his plan to compose a concerto, commenting that he needed only “a few days in a good mood” in order to bring him something of the sort. Those few days were years in the offing. It wasn’t until July 1844 that he was able to work seriously on the Concerto. On September 2 he reported to David that he would bring some new things for him; two weeks later the Concerto was finished.

As Mendelssohn’s adviser on matters of technical detail for the solo part, David must have motivated the composer’s decision to avoid sheer virtuosic difficulty for its own sake. In fact he claimed that his suggestions led directly to the Concerto’s subsequent popularity by making it so playable. It is no accident that Mendelssohn’s Concerto remains the first major Romantic violin concerto that most students learn.

At the same time, it is quite simply one of the most original and attractive concertos ever written. The originality comes from the new ways Mendelssohn found to solve old problems with the structural plan of the concerto form.

The traditional concerto built its first movement on a formal pattern that alternated statements by the full orchestra (ritornellos) with sections featuring the soloist. Over time, the orchestral ritornello got longer and longer, and the soloist wasn’t heard from for many minutes into the concerto. Mendelssohn takes the radical step of dispensing with the ritornello entirely. He fuses the opening statement of orchestra and soloist into a single exposition. The soloist enters with the main theme after just two measures of orchestral “curtain,” an idea that was part of Mendelssohn’s design from the very beginning.

Mendelssohn also approached the cadenza in a new way. Normally the orchestra pauses just before the end of the movement on a chord that is the traditional signal for the soloist to take off on his own. Mendelssohn’s solution is simple, logical, and unique: he writes his own cadenza for the first movement, but instead of making it an afterthought, he places it in the heart of the movement, where it completes the development and inaugurates the recapitulation. Never before that time—and rarely afterwards—has another cadenza ever played so central a role in the structure of a concerto.

Finally, Mendelssohn was an innovator with his concertos through his choice to link all the movements together without a break, a pattern that had been used earlier in such atypical works as Weber’s Konzertstück for piano and orchestra, but never in a work having the temerity to call itself a concerto.

The smooth discourse of the first movement, the way Mendelssohn picks up short motives from the principal theme to punctuate extensions, requires no highlighting. At the arrival of the second theme—which is in the relative major key of G—the solo violin soars up to high C just before the arrival of the new key and then floats gently downward to its very lowest note, on the open G string, as the clarinets and flutes sing the tranquil new melody. Mendelssohn uses the solo violin—an instrument which we usually consider a high voice—to supply the bass note under the first phrase; it is an inversion of our normal expectations, and it works beautifully.

When the first movement comes to its vigorous conclusion, the first bassoon fails to cut off with the rest of the orchestra, but holds its note into what would normally be silence. A few measures of modulation lead naturally to C major and the lyrical second movement, the character of which darkens only with the appearance of trumpets and timpani, seconded by string tremolos, in the middle section. Once again at the end of the movement, there is only the briefest possible break; then the soloist and orchestral strings play a brief transition which allows a return to the key of E (this time in the major mode) for the lively finale, one of those brilliantly light and fleet-footed examples of “fairy music” that Mendelssohn made so uniquely his own.

— © Steven Ledbetter

Serge Koussevitzky, c. 1949 by an unknown photographer. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, George Grantham Bain Collection. Koussevitsky commissioned Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra, giving the ailing composer a new lease on life.

Béla Bartók

Concerto for Orchestra, BB 123

Béla Bartók was born in Nagyszentmiklós, Transylvania (then part of Hungary but now in Romania), on March 25, 1881, and died in New York on September 26, 1945. The Concerto for Orchestra was commissioned in the spring of 1943 by Serge Koussevitzky through the Koussevitzky Music Foundation in memory of Natalie Koussevitzky. Bartók composed the work between August 15 and October 8, 1943; Koussevitzky led the Boston Symphony Orchestra in the first performance on December 1, 1944. The Concerto for Orchestra is scored for three flutes (third doubling piccolo), three oboes (third doubling English horn), three clarinets (third doubling bass clarinet), three bassoons (third doubling contrabassoon), four horns, three trumpets (with a fourth trumpet marked ad lib.), three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, two harps, and strings.

Early in the 1940s, with World War II raging in Europe, Béla Bartók immigrated to the United States, where he had a position doing research on recordings of Eastern European folk songs housed at Columbia University. He had all but given up composition during the preceding years, depressed by the state of Europe and by his own financial insecurity. Worse, he had begun to have a series of irregular high fevers that doctors were unable to diagnose, but which turned out to be the first indication of leukemia. The medical men were unable to do much, yet a powerful remedy in spring 1943 came not from a doctor, but rather from a conductor—Serge Koussevitzky.

Koussevitzky offered Bartók $1,000 to write a new orchestral piece with a guarantee of a performance by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The commission was a tonic for the ailing composer; at once he was filled with ideas for a new composition, which he composed in just eight weeks while resting at a sanatorium at Lake Saranac in upstate New York.

For the first performance Bartók wrote a commentary printed in the orchestra’s program book, something he rarely did. His summary of the spirit of the work was no doubt a response to his own feeling of recuperation as he composed it:

The general mood of the work represents, apart from the jesting second movement, a gradual transition from the sternness of the first movement and the lugubrious death-song of the third, to the life-assertion of the last one . . . .

He paired the first and fifth movements, as well as the second and fourth, so that the overall structure is a symmetrical pattern balanced through the middle; this was a favorite design in his multi-movement works.

The Concerto opens with a mysterious introduction offering forth the essential motivic ideas: a theme built up of intervals of the fourth answered by symmetrical contrary motion in seconds. These ideas become gradually more energetic until they explode in the vigorous principal theme in the strings, a tune that bears the imprint of Bartók’s musical physiognomy. The solo trombone introduces a fanfare-like figure, again built of fourths, that will come to play an important role in the brass later on. A contrasting theme appears in the form of a gently rocking idea first heard in the oboe. Most of these materials make their first impression as melodies pure and simple, but Bartók works out a wondrously rich concoction with all kinds of contrapuntal tricks.

The second movement, Giuoco della coppie (Game of Pairs), is simple but original in form, a chain-like sequence of melodies in folk style presented by five pairs of instruments, each pair playing in parallel motion at a different interval: the bassoons in sixths, then oboes in thirds, clarinets in sevenths, flutes in fifths, and trumpets in seconds. After a brass chorale in the middle of the movement, the entire sequence of tunes is repeated with more elaborate scoring.

The third movement, Elegia, is one of those expressive “night music” movements that Bartók delighted in. He described it as built of three themes appearing successively, framed “by a misty texture of rudimentary motifs.” The thematic ideas are closely related to those of the first movement, but they are treated here in a kind of expressive recitative of the type that Bartók called “parlando rubato,” a style that he found characteristic of much Hungarian music.

The Intermezzo interrotto (Interrupted intermezzo) alternates two very different themes: a rather choppy one first heard in the oboe, then a flowing, lush, romantic one that is Bartók’s gift to the often beleaguered viola section. But after these ideas have been stated in an A-B-A pattern, there is a sudden interruption in the form of a vulgar, simple-minded tune that descends the scale in stepwise motion. This tune actually comes from the Seventh Symphony of Dmitri Shostakovich. According to Bartók’s son Péter, Bartók was so incensed with the theme’s ludicrous simplicity that he decided to work it into his new piece and burlesque it with nose-thumbing jibes in the form of cackling trills from the woodwinds, raspberries from the low brass, and chattering commentary from the strings. Soon, however, all settles back to normal with a final statement of the two main tunes.

The last movement begins with dance rhythms in a characteristic Bartókian perpetuo moto that rushes on and on, throwing off various motives that gradually solidify into themes, the most important of which appears in the trumpet and turns into a massive fugue, complicated and richly wrought, but building up naturally to a splendidly sonorous climax. — © Steven Ledbetter

Ana Isabella España is a violinist from New York City enrolled in the Columbia- Juilliard exchange program, where she studies with Professor Kawasaki. She won first prize in the 2024 Sphinx Competition’s Junior Division and has appeared on Good Morning America, Telemundo, and the Kelly Clarkson Show with Yannick Nézet-Séguin discussing her co-authored book Who is Florence Price? She has appeared with major orchestras, and made her Carnegie Hall debut in March 2025 with the NY Youth Symphony. Isabella is Concertmaster of NYYS and previously held the role with the NY Philharmonic Youth Festival Orchestra under Gustavo Dudamel and NYO-USA under Marin Alsop. Isabella attends Aspen with a Talented Students in the Arts Initiative scholarship, which is a collaboration of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the Surdna Foundation Scholarship.

Heidi Cahyadi is a conductor and cellist from Indonesia. She made her debut conducting Dvorák’s Eighth Symphony in 2022 while pursuing her undergraduate degree in cello performance at Biola University in Los Angeles. She then attended Monteux Music Festival, where she worked with Tiffany Lu, Hugh Wolff, Kenneth Kiesler, Arthur Fagen, and Markand Thakar. Influential mentors include Daniel Brier, Leonardo Altino, Marlin Owen, and Budi Prabowo. Cahyadi returns to the Aspen Music Festival as a recipient of the 2024 Robert J. Harth Prize and will begin studying for her master’s in orchestral conducting at Indiana University this fall.

Giovanni Fanizza will join the Jette Parker Artists Program at the Royal Opera House in London for the 2025–2027 seasons, where he collaborates with the Royal Ballet. He is a 2025 Conducting Fellow at the Aspen Music Festival. He joined the Gstaad Conducting Academy in 2024, working with Johannes Schlaefli and Jaap van Zweden. In 2024–25 he interned at the Grand Théâtre de Genève for the production of Salome under Jukka-Pekka Saraste. He is currently completing a Master of Arts in Orchestral Conducting at the Haute école de musique de Genève with Laurent Gay. Giovanni Fanizza’s work in the Aspen Conducting Academy is supported by a Luciano and Giancarla Berti Scholarship and a fellowship in honor of Jorge Mester.

Ricardo Ferro is a Venezuelan-Canadian conductor, composer, and pianist. Recent and upcoming performance engagements include conducting appearances with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra and the Tonkünstler Orchestra at the Grafenegg Festival in Vienna as well as premieres of his works by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Dallas Symphony Orchestra, and the Canadian League of Composers. Ricardo received his master’s degree in composition from The Juilliard School in 2024, where he is now pursuing a second master’s degree in orchestral conducting. Upon obtaining his bachelor’s degree, Ricardo received the Canadian Governor General’s Silver Medal. Ricardo’s time in Aspen is supported by a Helen F. Whitaker Fellowship.

Tobias Gjedrem Furholt is a Norwegian conductor and percussionist. He started conducting concerts at age fourteen. He has been mentored by Bjarte Engeset since age seventeen. Tobias has conducted orchestras such as Stavanger Symphony Orchestra, Aarhus Symphony Orchestra, and Iceland Symphony Orchestra. Tobias is also a versatile percussionist. He completed his bachelor of percussion at the Stuttgart Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst (University for Music and Performing Arts) with the highest grade. In addition to appearances as soloist and ensemble musician, he has performed with orchestras such as the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, Ensemble Modern, Staatsorchester Stuttgart, and Bachakademie Stuttgart. His summer at Aspen is supported by a Lionel Newman Conducting Fellowship.

Mariano García Valladares is a Mexican conductor trained under Iván López Reynoso. He has served as assistant conductor at the Ópera de Bellas Artes in Mexico City and has led concerts with major orchestras in Mexico. Later this year he will make his international debut at the Teatro de la Maestranza in Seville conducting Mozart’s Don Giovanni. He returns to Aspen this summer after receiving the Robert Spano Conducting Prize, an award given by Mrs. Mercedes T. Bass.

Malaysian-born Tengku Irfan has appeared around the world as a conductor, pianist, and composer. A graduate of The Juilliard School, he is now the founder and music director of Ensemble Fantasque in New York City, which promotes twentieth and twenty-first century music. He appeared as a cover conductor with the New York Philharmonic and the National Symphony Orchestra, and as a guest conductor of Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra. In 2023 he was the assistant conductor of the National Youth Orchestra of the U.S. He is also a recipient of the Bayreuth Stipendium and the Robert Craft Igor Stravinsky Grant. Irfan’s work in the Aspen Conducting Academy is supported by the Scott Dunn Scholarship.

Hong Kong-born conductor and violinist Enoch Li is a Harvard/New England Conservatory dual degree program candidate pursuing a bachelor’s in mathematics and a master’s in violin performance under Nicholas Kitchen. Enoch’s conducting teachers include Yip Wai Hong, Samuel Pang, and Federico Cortese, and he has been selected for masterclasses with Tim Redmond, Mark Laycock, Joseph Bastian, David Itkin, and Michaelis Economou. He is the conductor of multiple orchestras and opera companies at Harvard, and has also conducted the Cyprus Symphony Orchestra, PKF-Prague Philharmonia, Asian Youth Orchestra, and the University of North Texas Symphony Orchestra. Li is a 2025 recipient of the David A. Karetsky Memorial Fellowship for a Young Conductor.

Michelle Di Russo is known for her compelling interpretations, passionate musicality, and championing of contemporary music. Di Russo will begin her tenure as Music Director of the Delaware Symphony in the 2025–26 season while continuing as associate conductor of the Fort Worth Symphony. She is a two-time recipient of the Solti Foundation’s U.S. Career Assistance Award, a former Dudamel Fellow with LA Philharmonic, a Taki Alsop Mentee, and has been a fellow of the Verbier Festival, the Chicago Sinfonietta program, and the Dallas Opera Hart Institute. This summer she is the recipient of a Con-ducting Academy Fellowship in memory of Jack Strandberg.

Japanese-American conductor Ken Yanagisawa is music director of the Boston Opera Collaborative and the Boston Annex Players, associate conductor of the Boston Civic Symphony, assistant conductor of the New Philharmonia Orchestra, and assistant professor at Berklee College of Music. A 2024 Aspen Conducting Academy Fellow and James Conlon Conductor Prize recipient, Ken has previously served as a conducting apprentice with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and has assisted/covered at the National Symphony Orchestra, Rhode Island Philharmonic, Berlin Academy of American Music, and Opernfest, among others. Ken holds a Doctor of Musical Arts in Orchestral Conducting from Boston University..